Cover me!

Here's looking at you, book

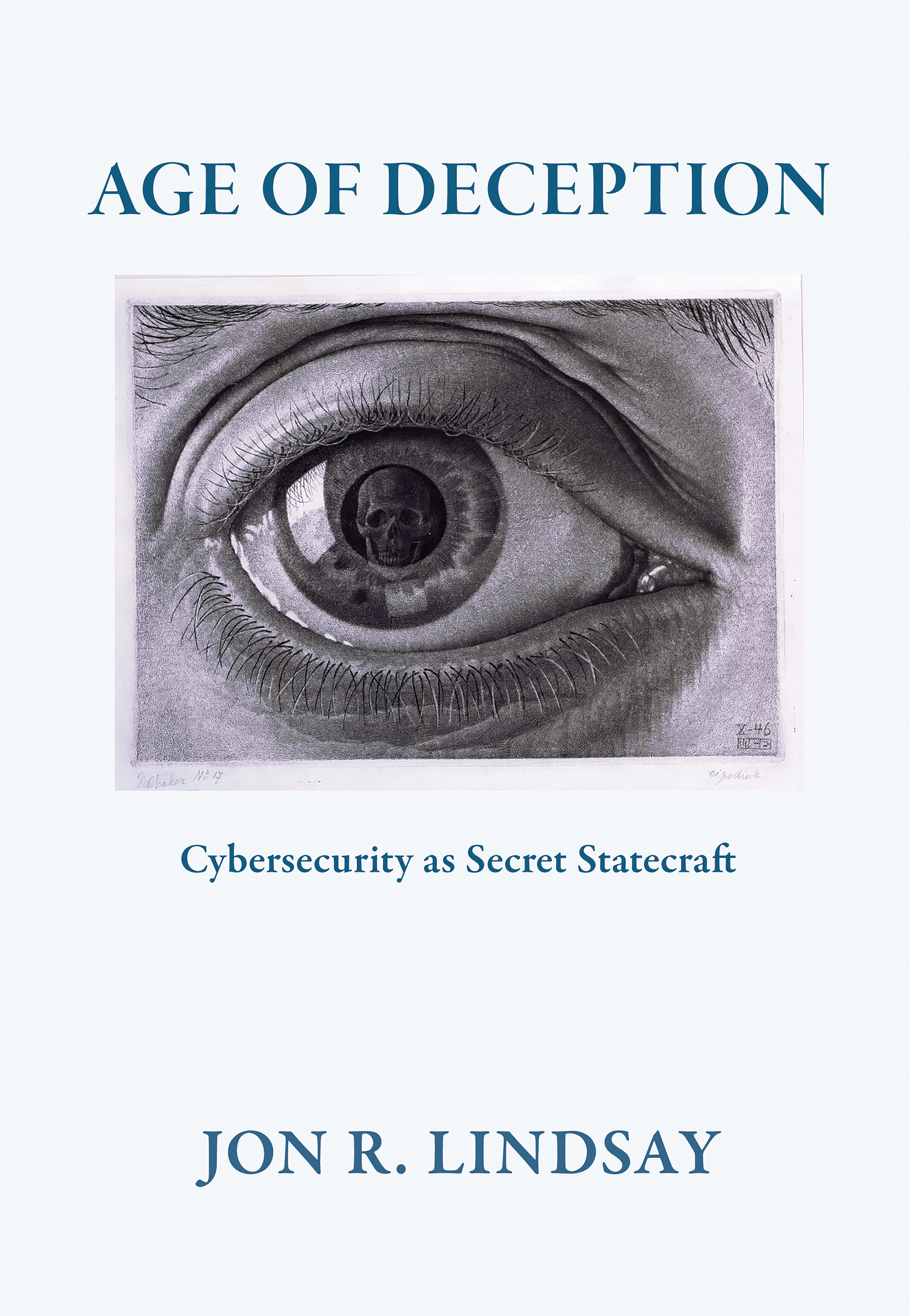

I am happy to announce that Age of Deception officially has a cover:

I am excited about this for many reasons. First, I am relieved to have a book about cybersecurity with nary a microchip, keyboard, mouse, wire, datastream, glowing globe, or hoody-wearing hacker anywhere to be found. The visual cliches of cyberspace are hard to escape, and I had to battle to keep them at bay, but escape them we did.

Second, as General von Moltke the Elder may have said, that which is simple is also good. There is already a lot going on in this book, so I didn’t want a lot going on on the cover. Also, there is a lot going on the Escher drawing (more on that next), so I didn’t want to take anything away from its intrinsic depth. The simplicity of an old black and white drawing on a book about high tech politics also helps to make the case that the most interesting things about cybersecurity actually have nothing to do with technology, and everything to do with much older forms of politics. The simple cover design emphasizes the classic nature of secret statecraft, regardless of its technological manifestation.

Third, Eye by M.C. Escher is just a remarkable image. When I was playing with cover ideas, I found myself drawn to Escher. He has long been one of my favorite artists, embodying a union of creative art and precision draftsmanship. Escher is an interdisciplinary artist, and this is an interdisciplinary book. Escher is obsessed with recursive paradoxes and visual play, which abound both in the book and in my brain. Also, I gave early presentations of this book in a conference in The Hague, which is where the M.C. Escher museum is located, and where you can see the original Eye drawing.

Many of Escher’s images would have worked for this book, particularly his metamorphosis series for the transformation of ancient espionage into modern cybersecurity, but I was instantly captivated by Eye as soon as I saw it. In many ways, it is a perfect image for a book about the dangers of information technology. The eye is the organ of perception, and hidden within the window of the soul is a subversive symbol of death. Information technology is likewise the soul of globalization, enabling perception and communication, yes, but also surveillance, subversion, and exploitation. Eye is a drawing, of course, so we are looking at a technology of perception here, which means that the mortal threat within is something of our own making. And that is a theme that runs through Age of Deception: we willingly build and use the technologies that are coopted to exploit us. In cybersecurity, and in intelligence more broadly, we are willing collaborators in our own deception.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about Eye is its layers of reflection across space and time. It is literally a self portrait by Escher of his own eye reflected in a shaving mirror. The eye is in exquisite, photo-like realism, which makes the fanciful skull all the more striking, as if it must be there in the original reflection. Yet what exactly is being reflected? When you look at the drawing, you the viewer occupy the same position that Escher the artist had while drawing it, so you might be looking at his eye, or you might be him looking at your own eye. Looking at it today is especially spooky since Escher is long dead, and here you are in his place: are you seeing death in his eye, or your own? The dark mortality that stalks us all stares out from an infinite regress of reflections.

Fourth, the baby blue of the background, which the designer at Cornell chose to make the book’s outline stand out from the white backgrounds of webpages, creates a nice effect. The softness and innocence of baby blue speaks to the superficial attractiveness and harmlessness of cyber technologies. But what I really like about it is that the blue background makes the black and white drawing look a little pink. Do you see this effect, too? Pink is a complementary color to blue, and so the eye sees it in the grey of…the Eye, even though it is not actually there. Like so many visual illusions, this makes the point that perception is an active constructive process, and we can be led by our own complicit construction.

The illusion of pink on the blue background might also suggest some interesting gender commentary on cybersecurity. There are a lot of ways to unpack this. Computer science generally and cybersecurity remain male dominated fields. In computing history, of course, “computer” was a job description held by predominantly female clerks working on tabulation machines. Men built machines while women did the operational work, which is why many early software pioneers like Grace Hopper were women. But as software came to be seen as a lucrative source of power, men took over, and now Silicon Valley is run by tech bros. So the “pink” of information technology is as illusory as the early dreams of liberation and empowerment that accompanied the early internet, which is now swept away by the dominance of “blue” throughout the tech field.

Yet another way to interpret this through a gendered lens is that cybersecurity depends on hidden work. I have always been interested in the hidden work that makes information systems work, and this hidden work is what makes exploitation both hard and difficult. So while I don’t explicitly frame it as such in this book (or in Information Technology and Military Power for that point), the general STS orientation of the book is certainly informed by the feminist move of revealing the practical work, care, and exploitation that is hidden in plain sight.

Finally, the other gendered interpretation that comes to mind is that deception has long been stereotypically represented in feminine terms. In Homeric myth, for instance, male warriors fight bravely face to face with spears and shields, while female warriors rely on guile and deception, such as Penelope unweaving her web or Circe (and Helen) using potions and poisons. So secret statecraft is the more feminine face of statecraft, compared to the more masculine archetypes of war and coercive diplomacy. What all three of these ideas have in common is an emphasis on the hidden, the overlooked, the ambiguous, the deceptive, and the complicated as fundamental features of both technology and politics.

So there are a few reasons why I like this cover. I hope you like it, too. And I hope that you will like what is inside the cover as well. An actual book should follow very soon, hopefully released by October. You can preorder here (including a free version of the eBook).